Published: 7 April 2018

Last updated: 4 March 2024

In a Skype interview from Warsaw, Gross is professorial and urbane. He speaks vigorously, his Eastern European accent adding a sense distinction to his articulate English. He is in Poland to participate in the commemoration of the events of March, 1968, when Polish students demonstrated against the communist regime and its campaign of censorship. Then a physics student in Warsaw, Gross had been involved in the protest movement, expelled from the university and jailed for several months.

He says he still has “wonderful friends in Poland, and I am enjoying myself, going from one celebration of the events of 1968 to another. But this anniversary is marred because the government, led by the Law and Justice Party, is undermining free speech and attempting to create ideological control. I am very, very worried for Poland.”

The most recent legislation is motivated, Gross explains, by domestic politics as the ruling party panders to its right-wing constituency. But it could have been written to squelch Gross himself, who came to international academic and political prominence with the publication of three historical books that have forced Polish citizens to face the reality of their behaviour during the Holocaust and the reality of Polish anti-Semitism before, during and after the war.

Soviet control crushed any public discussion about the Holocaust, anti-Semitism or Polish culpability, enabling Poles to entrench their view of themselves as noble, heroic victims and to repress the anti-Semitism that had always been part of Polish history.

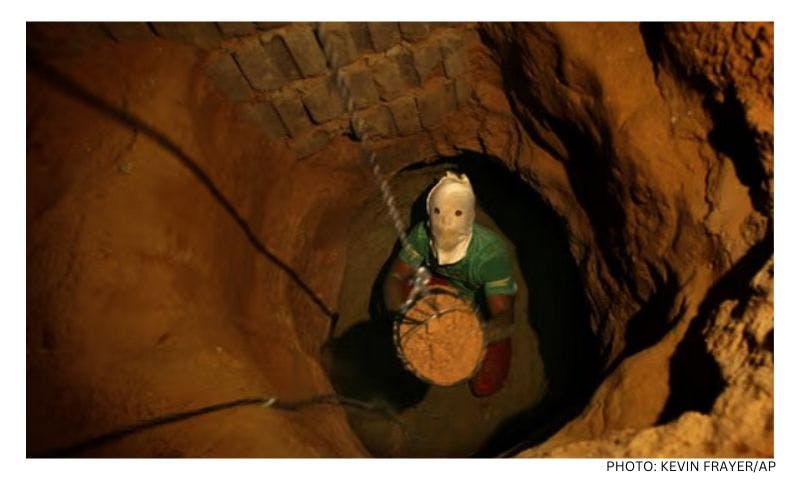

In the first of these three books, Neighbours, published in 2001, Gross described in passionate, almost vulgarly brutal prose the massacre of Polish Jews by their neighbours in the village of Jedwabne in July, 1941. In Fear: Anti-Semitism in Poland after Auschwitz, (2006) he detailed how Poles had attacked Jews who returned to Poland after the Holocaust, and, in particular, the story of the Kielce pogrom in July, 1946, when ethnic Poles murdered 37 Jews. In Golden Harvest, published in 2012 together with his wife, Irena Grudsinska Gross, he claimed that Polish peasants exploited Jews during the Holocaust and then afterwards dug up mass graves of Jewish victims in a search for gold.

Poles’ reactions to the publications of these books have been intense. For some, they represented an opportunity for Poland to come to terms with its difficult past. But others viewed Gross as a traitor who was besmirching Poland and the Poles, who were themselves, they argued, the victims of the Nazis. Polish officials even investigated the facts of these cases to consider prosecution of Gross for defamation of the Polish population, although no charges were ever brought.

But as Poland, like so many other countries, and especially in Eastern Europe, becomes increasingly nationalistic, opposition to Gross and his scholarship is intensifying. Last year, the Polish government threatened to strip him of the Order of Merit of the Republic of Poland, which he was awarded in 1996 for his activities in opposition to communism. And although he describes the incidents matter-of-factly, each time that Gross comes to Poland he is called into the police for questioning and there are public calls to strip him of his citizenship.

“I suppose that one day I might be prosecuted, but that would be just a small distraction in the face of the attempts by this government to destroy Polish democracy,” he says dryly.

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="18547"]

Born to an ethnic Polish mother, who had been a member of the Polish resistance, and a Polish-Jewish father, Gross left with his family after the events of 1968. Resettling in the US, he earned a PhD in sociology from Yale University, then taught at several Ivy League colleges before assuming his current position at Princeton. The question of how societies accommodate, collaborate and resist in the face of totalitarianism was central to his doctoral work at Yale and to his subsequent research.

After World War II, Gross explains, Western nations were able to reflect and consider their own roles. But Soviet control crushed any public discussion in Poland about the war, the Holocaust, anti-Semitism or Polish culpability, enabling Poles to entrench their view of themselves as noble, heroic victims and to ignore, then repress, the anti-Semitism that had always been part of Polish history.

Yet, since fall of the Communist bloc, and especially in the past two decades, Poland has experienced a rediscovery of its Jewish history, as indicated, for example, by the Polin Museum of the history of Polish Jews in Warsaw, which presents, according to its website, “a 1000-year history of Polish Jews” In an almost philo-Semitic movement, many Poles have discovered their own personal Jewish roots and celebrate Jewish culture in numerous festivals throughout the country.

After 50 years of repression, Polish intellectuals began to study the role of the Polish people during the Holocaust. “Over the past 20 years in Poland, more than in any other country or in any other language, there has been a fantastic proliferation of historical and artistic work to explore the issue of complicity and participation and the evil deeds committed by Christian society against the Jews,” says Gross.

“My identity as a Pole includes a profound sense of siding with the persecuted. And few have a better historical right than the Poles to feel persecuted. But being Polish carries a responsibility, a need to sort out what we have done. We cannot base our self-identity on lies or half-truths. We did these things. They happened in the streets and villages, where everybody could see. The anti-Semitism is incomprehensible; it is beyond the pale. It is a blemish on our humanity, a scandal to our minds.

“As Poles, we have a collective sense of identity, which must include not only Polish victimhood, but also Poles as perpetrators. It is possible to be both a noble hero and a villain, and we have been both. We must accept this.”

[gallery size="medium" ids="18548,18549,18550"]

But this process of historiography and soul-searching, Gross says, has also lead to a backlash among the nationalistic segments of Polish society. “The Law and Justice party is taking advantage of this. There is a resurgence of populist and nationalist trends, and, except for Hungary, I do not see any country in which the ruling party believes that democratic and liberal institutions must be so destroyed and degraded. Here in Poland, the party is deliberately exploiting this nationalism and xenophobia to create autocratic rule.”

The party, he says, is “playing to nationalistic Polish pride by painting a picture of Polish innocence that has no blemish, made up only of victimisation and heroism. To accomplish this, they must reframe the understanding of the war, and especially with regard to the attitudes and complicity of segments of Polish society towards their fellow Jewish citizens.”

The regime, he says, “claims that they have instituted this law in order to prevent the use of the term ‘Polish extermination camps.’ But this is merely a spurious explanation, since no one uses the phrase anyway. And no-one is seriously saying that Poland as a country was complicit – Poland was under a horrendous Nazi occupation. And the term doesn’t even appear in the legislation.”

In response, he says, Poland has seen a terrible increase, in public space and social media, of anti-Semitic statements, and this is very ugly. “I have read many hundreds of survivors’ testimonies; in every one, the Jewish survivor described betrayal or blackmail by a fellow Polish citizen. Some also found a good person who helped them survive. But the government is denying them the right to tell their own experiences. Once again, Jews do not feel safe in Poland. This is intolerable.”

When asked “why now?”, Gross acknowledges that “to be honest, I do not understand the timing. The law was formulated about a year and a half ago. But it is clear that the harsh, xenophobic line seems to be working for the party. They won the elections by taking a harsh stance against refugees from Europe and the relocation of anybody into Poland, which flies in the face of EU policies and also of what should be done.”

The widespread condemnation of the new law has, in many ways, played right into the hands of the government. “It enables them to portray Poland as under attack from outsiders and foreign powers and to present themselves as the defenders of Polish pride and purity.”

Yet, he says, the condemnations are crucially important. “This government will do whatever it wants to anyway and they don’t need excuses. But it is important to show this government that the world will not support it. And even more importantly – there is a tremendous push-back against the law from the open-minded sectors of Polish society – the media, intellectuals, academia. They must know that the world is behind them, so that they can continue to tell the truth.”

Main photo: Times of Israel